Missing Persons

Some disappearances are more subtle than others. Faculty detectives seek—through images, language, and stories—evidence of vanished people.

(Photo composite courtesy of Ronald Coddington/Military Images Magazine)

Portraits of the Past: Civil War Soldiers

Oliver Croxton looks pensive. His light, deep-set eyes gaze to the left of the camera; his cheekbones show prominently above his dark, bushy beard. The two chevrons on his uniform sleeve reveal his corporal status.

More than 150 years after Croxton sat for his portrait, his great-great-great nephew came across it, and for Kurt Luther, the moment was electrifying.

“It was serendipity at play,” Luther says. “I happened upon a photo album of Oliver’s Union regiment in a museum exhibit. There he was in his Civil War uniform; no one in my family had ever laid eyes on him before.”

Luther, an assistant professor of both computer science and history at Virginia Tech, had long been interested in the Civil War. But now he became obsessed with offering that same thrill of discovery to others.

“It’s so powerful to look into the faces of these soldiers,” Luther says. “And yet, at most, only 30 percent of the photos of Civil War soldiers are identified. I realized we could use new technologies to help put names to faces.”

So, in 2017, Luther joined with Paul Quigley, director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, and Ronald Coddington, editor of Military Images Magazine, to launch Civil War Photo Sleuth. The website uses two principal tools—facial-recognition software and crowdsourcing—to allow academics and members of the public alike to do the historical detective work.

The site can scan the facial features of soldiers and compare that facial “map” with those of thousands of other images in the database. Contributors can upload photos found in attics or scattered among the online databases of historical societies, museums, and collections. The photos can then be tagged with such details as the number of chevrons on uniforms and the style of hat insignia.

“Users often search the database for photos of their ancestors or for soldiers who served in local regiments,” says Luther. “That discovery process is one of the great joys of photo sleuthing. And the site allows us to restore meaning to images and personal histories that would otherwise remain forgotten.”

Civil War Photo Sleuth now includes the photos of more than 20,000 identified soldiers, along with 5,000 others waiting to be recognized, including some civilians. More intriguing prospects are uploaded every day.

“One of the things that makes history so exciting is getting to know people from the past as people,” says Quigley, who also serves as the James I. Robertson Jr. Associate Professor of Civil War Studies in the Virginia Tech Department of History. “A photo makes a connection so much more direct. You can really imagine these people as complex human beings rather than just names in documents.”

Principals Charles L. Marshall (front row on the left) and Edgar A. Long (front row, second from right) gather with teachers in front of a Christiansburg Institute classroom building. (Photo courtesy of the Christiansburg Institute Historical Photograph Collection; digital image courtesy of Special Collections, University Libraries, Virginia Tech)

Separate Histories: African Americans with Unchronicled Achievements

The fifth graders were assigned a case with few clues. If this place could talk, they were asked, what would it tell you about the people who were here a century ago?

The students stood in a field with long, matted grass. A thicket of trees encircled much of the site. To the north, they could see scattered industrial projects and commercial buildings; from the south, they could hear trains lumbering past. On the far end of the property, a large bell was visible near a reconstructed smokehouse. Near the center of the field sat a two-story brick building with boarded-up windows.

And then, slowly, other clues accrued—and history came to life.

The landscape changed for the students. Through the use of mobile devices and an augmented-reality app, they could see the desolate field in front of them layered with computer-generated images of structures that had once stood there. The fifth graders soon realized they were on a former school campus. Yet that was just the beginning of their understanding.

“The campus was mostly missing,” says David Hicks, a professor in the Virginia Tech School of Education, “so we decided to present the what and the who as historical mysteries, with the students acting as junior detectives. We wanted to use new technologies to make the invisible past visible again. That’s how CI-Spy was born.”

Hicks was part of a team of historians, computer scientists, and fifth-grade teachers who, with National Science Foundation funding, designed and developed the app, which also provided historical documents, photographs, and oral-history interviews. Students then used a set of guiding questions to analyze the material.

The CI-Spy app was named for the former school—the Christiansburg Institute. Founded in 1866 with the mission of educating the children of former slaves in the Appalachian region of Virginia, the school began as a one-room rented log cabin. By the turn of the century, it had expanded into a sprawling, 185-acre campus with more than a dozen structures, including classroom buildings, a dormitory, a woodshop, and a gymnasium.

Generations of African Americans studied there under the leadership of such noted educators as Booker T. Washington. Then, after a century of serving as the principal segregated school for African American students across southwestern Virginia, the Christiansburg Institute closed its doors in 1966, following desegregation of the area’s schools.

“We didn’t tell the students that the Christiansburg Institute was a segregated school, because we thought it would be more powerful for them to discover that for themselves,” Hicks says. “CI-Spy helped the students understand how the separate-but-equal doctrine—particularly segregated schooling—affected their own community.”

Over time, most of the school’s buildings were sold or torn down. Today, the Edgar A. Long Building is the lone classroom facility still standing, and the smokehouse has been converted into a small museum. Christiansburg Institute, Inc. and the Christiansburg Institute Alumni Association—both of which partnered with the development team in creating CI-Spy—are working to raise funds for renovations and, eventually, educational programming.

“The mixed-reality technologies allowed us to layer in information to help the fifth graders hone their detective skills,” Hicks says. “And, we hope, the hidden histories that revealed themselves gave the students an appreciation for the lives of African Americans during those years of segregation.”

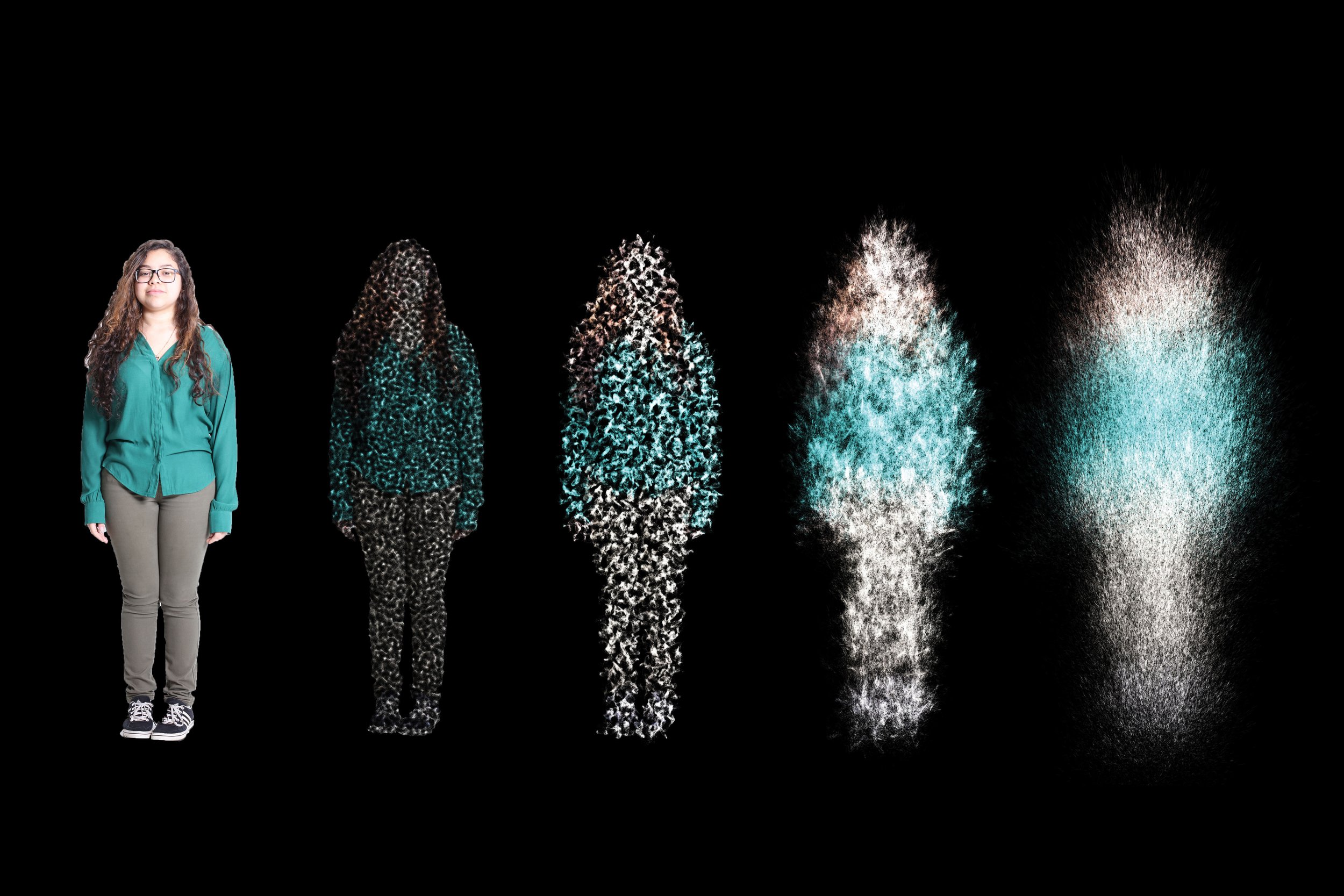

In “The Reminiscence,” a digital reboot of the posture-portrait-taking practice of the past, a new generation of students dissolved their photos into scattered pixels to represent the destruction of appropriated images. (Photo courtesy of Connecticut College)

Stolen Identities: Women and Men with Appropriated Images

Imagine being led to a windowless room, told to strip, and instructed to turn left, right, and center as someone photographed you in the nude. And now imagine, after gathering your clothes again, being handed a grade.

A range of famous people—from Hillary Clinton and George H.W. Bush to Meryl Streep, Nora Ephron, and Bob Woodward—were subjected to such photo sessions during their college orientations. In fact, the practice of taking “posture portraits” was common at many Ivy League and Seven Sisters colleges between the late 1920s and mid-1960s.

“The program was run by physical education departments under the guise of promoting good health,” says Andrea Baldwin, an assistant professor in the Virginia Tech Department of Sociology. “If your posture received a failing grade, you’d have to take a class to ‘correct’ the deficiencies of your spine. Some schools wouldn’t allow you to graduate until you passed.”

Perhaps even worse than the humiliation, Baldwin says, was the possible impetus behind the posture portraits. Driving the practice was a psychologist, William Sheldon, who believed that physique determined a person’s destiny. He used the photographs to classify people by body type.

“At best, Sheldon’s work was based on faux science,” Baldwin says. “At worst, it was motivated by eugenics. Regardless of his real intentions, underlying the practice were assumptions of what it meant to be normal.”

Baldwin learned of the diagnostic practice while a visiting assistant professor at Connecticut College, which had followed the practice earlier in its history, when it was an all-women’s institution. She teamed up with a choreographer, a computer scientist, and students to delve further into the history.

“During our research into the archives of various schools and the Smithsonian Institution, where a number of the files ended up,” says Baldwin, “we were assured the photos had all been destroyed. Yet we came across hundreds of them. We were seeing women and men in the nude without their consent; we felt complicit.”

The researchers also interviewed Connecticut College alumnae who had undergone the practice. The women, whose ages ranged from 78 to 92, all regretted their compliance, even as they were given no choice. One participant characterized the experience as “dehumanizing”; another likened it to being arrested.

Baldwin points out that the dubious practice happened to mostly privileged college students. “Imagine,” she says, “what their vulnerability suggests for those not as protected by socioeconomic class or opportunity.”

So Baldwin and her colleagues decided to stage a photo session that allowed Connecticut College students to claim their own images as a kind of therapeutic reconciliation with the past.

“We wanted to heal this narrative of shame by using photography, dance, and technology to refocus the gaze,” Baldwin says. “In ‘The Reminiscence,’ we chose to do the opposite of everything those early photo sessions represented. Our participants wore whatever they liked and stood however they felt comfortable. The students of the past were silent; our students recorded their thoughts in their own voices.

“The past sessions sought conformity and compliance; we opted for individuality, freedom of choice, and—most significantly—consent.”

(Photo by Vandervelden/iStock)

Forgotten Plights: Refugees with Uncaptured Stories

“People see war on television, but they don’t smell it, they don’t hear it, they don’t feel the impact of a bomb,” Elvir Berbic says. “It’s so different when you are there, and you constantly have this fear. Thankfully, we were able to get out in time. Many people did not, of course.”

In 1992, when he was ten years old, Berbic and his family fled Bosnia in a small convoy of cars. He watched through the windows as they passed shot-up villages, charred houses, and the rotting carcasses of livestock. An explosive just missed their vehicle as they raced across the border.

Berbic’s family lived in a refugee camp in Croatia for three years, before making their way to Roanoke, Virginia. It was there he recently recounted his history to Katrina Powell, an English professor at Virginia Tech.

His story is now one of many that Powell and a team of Virginia Tech students are compiling in a book, Resettled: Beginning (Again) in Appalachia. Voice of Witness, a nonprofit that advances human rights through oral-history projects, is underwriting the project.

“Our book focuses on interviewing people resettled in Appalachia, whether a month ago or generations ago,” says Powell. “These stories carry importance beyond their intrinsic value. Both refugees and Appalachians get misrepresented in the news media all the time, for example.

“We want to amplify the voices of the unheard. Stories of immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers are multifaceted, and it’s critical to learn that complexity to ensure we have the most humane policies and laws possible.”

As part of the Voice of Witness grant, the Virginia Tech Center for Rhetoric in Society, which Powell directs, holds training workshops in oral-history methodology for both undergraduate and graduate students.

“Oral history is meant to document an individual’s story from birth to the present,” Powell says. “When you know the entirety of someone’s life, you understand better the impact of displacement and resettlement. When we grasp that impact, we’re more likely to treat people humanely and to gather as communities to welcome them.”

Berbic now enjoys welcoming others, particularly in his role as a volunteer soccer coach for teen refugees.

“I work with these young men because I was that person,” says Berbic, who has since earned a master’s degree and now works at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. “I want to help them focus on getting educated and assisting their families and communities. I give back this way because I remember those years when I had nobody to guide me.”

Hurricane Katrina damaged the old Holy Cross School in New Orleans so badly it has stood vacant ever since. (Jim West/Alamy)

Linguistic Losses: New Orleanians in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina

With its buoyant jazz beats, flamboyant Carnival floats, and piquant Creole dishes, the Big Easy has long been celebrated for its sensory exuberance. Yet some of the distinctive sounds of New Orleans—the linguistic cadences that reflect the city’s multicultural heritage—are slowly softening and even falling into silence. And at the epicenter of that loss is Hurricane Katrina.

“You can’t talk about life in New Orleans without talking about Katrina,” says linguist Katie Carmichael, an assistant professor of English at Virginia Tech. “It changed the trajectory of the city forever. People were forced to evacuate, and different ethnicities and groups dispersed. As the city embarked on its long road to recovery, it was forced to redefine itself.”

Carmichael focuses her research on linguistic changes that have occurred in the aftermath of the storm. And now, with a National Science Foundation grant she shares with Tulane University collaborator Nathalie Dajko, she is defining the effects that displacement and migration have had on language spoken in the city.

“The storm stirred up issues of gentrification, displacement, globalization, racial tension, social class, and politics,” Carmichael says. “It’s as if Katrina shook the city up and then set it back down, forcing people to confront these issues quickly. We’re now working against the clock to capture the corresponding linguistic changes.”

Carmichael and Dajko are interviewing 200 lifelong residents with different ethnic backgrounds and neighborhood origins to collect the largest and most diverse data sample ever assembled in the city. They’re also working with a team of undergraduate researchers from both Virginia Tech and Tulane to analyze those data.

“Social pressures affect languages everywhere,” Carmichael says, “but the hurricane accelerated those social pressures in New Orleans, so we can detect linguistic changes in real time.”

As part of their work, research team members are asking New Orleanians to characterize their language in their own words and to describe how different phrases and ways of speaking relate to their personal identities. Their narratives will be featured on a website.

Carmichael adds that everyone they interview shares a Katrina story.

“We hear the most heart-wrenching stories of people wading through floodwaters and losing family members,” Carmichael says. “Everyone down there has experienced deep, deep loss. It’s part of who they are now.”

This article appeared as part of “Watching the Detectives,” a special issue of the magazine of the Virginia Tech College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences.